BOTANICAL SABOTAGE: FOXTAILS

Foxtails might seem like no big deal, just some dry grass by the trail, right? But for our pets, they can cause some serious health issues. The tiny, barbed seed heads are designed to burrow which means once they get into a paw, ear, or nose, they can keep moving deeper. This can lead to infections, pain, and sometimes even needs surgery to remove them. The good news? A little awareness goes a long way in preventing foxtail injuries. We'll walk you through what foxtails are, where they hide, and how to help your pet avoid them, so you can both enjoy the outdoors without the surprise vet trip.

What Are Foxtails?

Foxtails are those spiky little seed clusters that come from certain types of wild grasses and weeds. They’re called foxtails because the seed heads look similar to the bushy tail of foxes. These plants grow all across the States, but they really thrive in dry areas out West (like California). You’ll usually find foxtails in open fields, along trails and roadsides, and in overgrown yards. They’re especially common during dry months in places like hiking trails, meadows, parks, and vacant lots. In the spring, foxtail grasses pop up as soft, green tufts which are totally harmless. But by late spring and into summer, they develop fuzzy, wheat-like heads that dry out into brittle clusters. As the plant matures and dries, the seed awns detach easily and hitchhike on animals, people, or even just the wind. Here’s where it gets tricky: “foxtail” isn’t one single plant. It’s more of a catch-all term for several grasses - like wild barleys and millets - that all produce the same kind of barbed seed awns. Awns are the sharp, needle-like bristles that make up the seed head. Thanks to the microscopic barbs that grip like fish hooks, foxtails are designed by nature to only move one direction. This mechanism is amazing for helping the seeds burrow into the soil and grow, but not so great when it ends up burrowing into fur or flesh. In short: when they’re green, foxtails are just grass. But once they dry out they become dangerous little darts looking for places to burrow so they can grow.

Why Are They Dangerous?

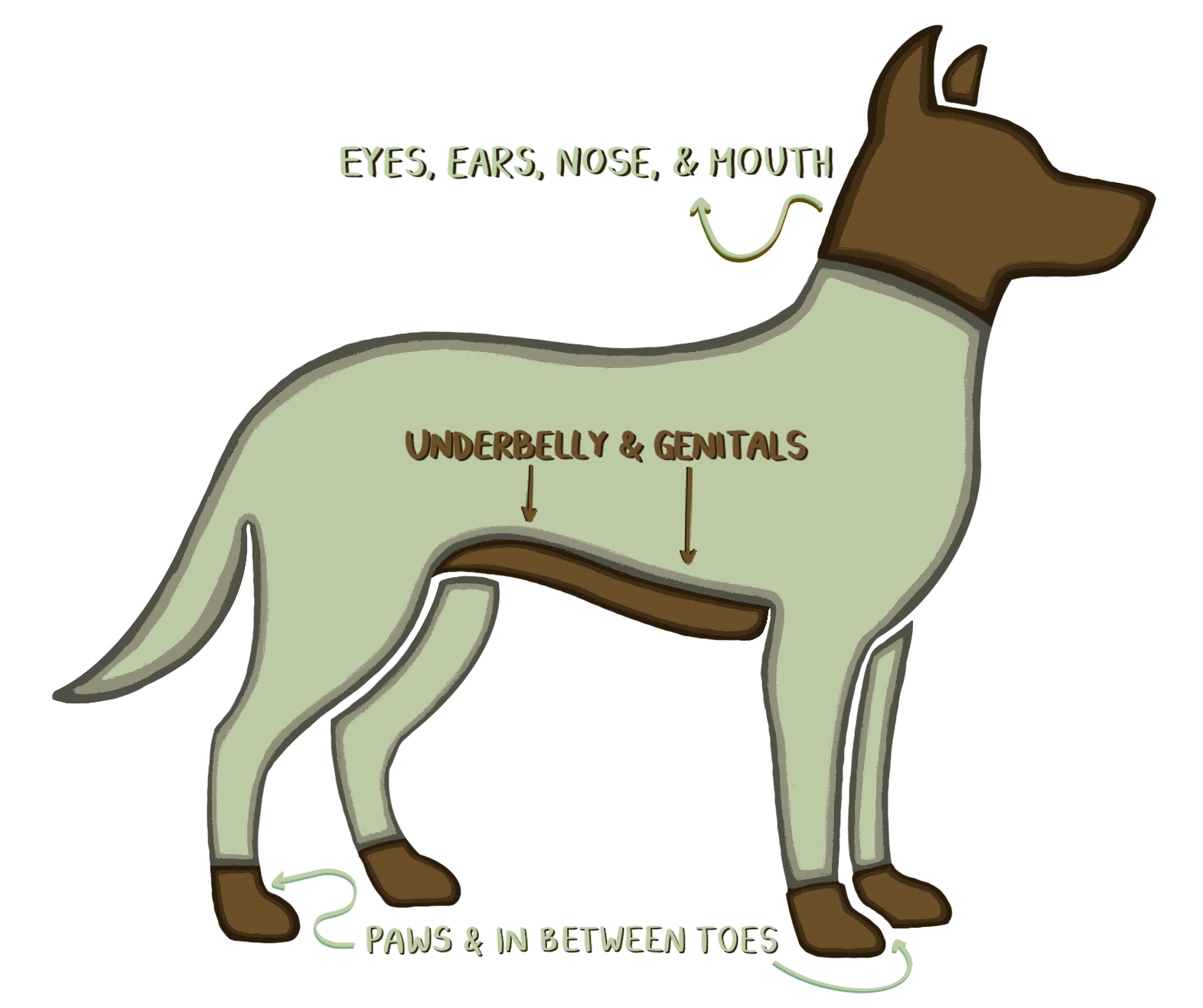

Foxtail related injuries are most commonly seen in dogs but can affect cats, livestock, and wildlife as well. These barbed grass awns most often enter the body through the nose, mouth, ears, or eyes but they can also puncture anywhere on the skin, leading to painful wounds or abscesses. Once embedded, their one-way design prevents them from backing out, allowing them to burrow deeper with time. In severe cases, migrating foxtails have been found in the lungs, brain, and other vital organs. The most common entry points include :

What Happens Inside the Body? Once a foxtail enters the body, it acts like a barbed splinter. As it migrates through tissue, it drags dirt and bacteria with it, often causing infection and abscesses. The body recognizes the awn as a foreign invader but it cannot easily break it down or push it out. Because of this the immune system either walls it off or allows it to continue migrating, sometimes into vital organs or body cavities. This makes foxtails extremely difficult to locate once they’ve moved inwards. If an awn reaches a vital organ or body cavity, it can cause severe conditions like pyothorax (pus in the chest cavity) or internal organ damage. Left untreated, internal foxtails can result in irreversible organ damage, systemic infection, and even death.

What Are The Clinical Symptoms?

Signs of a foxtail injury depend on where it entered the body, but they usually show up suddenly and get progress quickly. Because foxtails are sharp, barbed, and capable of deep migration, the symptoms can vary widely and are often mistaken for something minor. If one gets into a paw, you might notice your pet constantly licking, limping, or having swelling between the toes or on the paw pads. In the ears, it can cause head shaking, scratching, and sometimes a strong odor due to infection. In the eyes, foxtails can lead to squinting, tearing, rubbing at the face, or swelling that makes it hard to open the eye. If inhaled, they can cause sneezing fits, nosebleeds, yellow or green discharge, or your pet might start pawing at their nose to attempt to get it out. In the mouth or throat, you might see coughing, gagging, drooling, or trouble swallowing.

Foxtails can also sneak in through the skin, especially in spots with thin fur like the armpits, belly, or groin. This can cause swelling, painful lumps, or draining sores that may seem to move over time as the foxtail keeps burrowing. In some cases, they can enter the genital area and work their way into sensitive places, leading to extra licking, discharge, or more frequent urination. If the foxtail keeps migrating, it can reach deeper parts of the body like the lungs or stomach area, which can cause serious problems. More general signs may emerge later like tiredness, reduced appetite, a fever, or random swelling especially when the original entry site is no longer visible.

Because these symptoms can mimic other common issues, diagnosis can be difficult especially if exposure to foxtails wasn’t witnessed. That’s why it’s so important to have your pet checked out by a vet if you notice anything off. Depending on where the foxtail is, your vet might need to use tools to look inside the ears or nose, or even light sedation to search deeper. In more complicated cases, scans like x-rays or ultrasounds may be needed. Abscesses or infected sites may need to be flushed, and your pet may be sent home with antibiotics. The good news is that most pets recover quickly with proper treatment, but putting it off may lead to more serious issues or even surgery.

STILL HAVE QUESTIONS, CONTACT US! (707) 795-3694